Heavy with scuba gear, you make your way deeper and deeper into the coastal waters. For a while, the surface of the water is right above you, and the sun creates shimmering, broken ripples on the ocean ceiling. But soon enough, you catch a glimpse of an opening -- the entrance to a cavern. As you swim inside, various plants, unfamiliar fish and interesting rock formations like stalactites and stalagmites color the interior.

But this isn't your final stop. As you continue further, the surrounding area becomes darker and darker. A narrow, pitch-black hole is in your line of sight, and going into it will be a much more challenging and dangerous experience than what you've just been through. Because of the extreme darkness and potentially uncharted areas, you'll need lights, special equipment and loads of experience for the practice of cave diving.

Advertisement

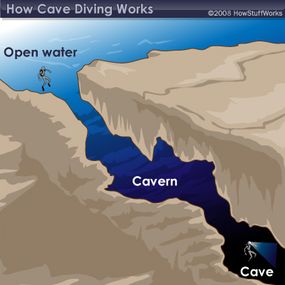

There are three main classifications of diving: cave diving, open-water diving and cavern diving. Open-water diving is where all divers start gaining experience, and it's defined as a dive in which linear access to the surface is directly available -- in other words, by swimming straight up, a diver should be able to get a head above water, and sunlight is easily visible. In cavern diving, on the other hand, a diver is exploring permanent, naturally occurring caverns and has a ceiling overhead, but an entrance and visible light from the sun are in sight. Both open-water diving and cavern diving are considered recreational activities that require recreational-level certifications and training, and divers usually limit descents to 130 feet.

Cave diving differs from the other two types of diving in that it's a form of technical diving instead of a recreational one. It requires a much different set of equipment and several years of training and certification, and professionals constantly stress the need for top-notch fitness and gear. But above all, they admire cave diving for its unique challenge and the potential to discover the undiscovered -- scientific research gathered from cave dives can lead to the study of rare organisms and even offer cures to diseases like leukemia.

How does equipment for cave diving differ from other recreational forms of diving? How do divers move around, despite low visibility and winding caves? To learn about cave diving, read the next page.

Advertisement