Advertisement

Tour Cliff Dwellings of the Ancestral Puebloans

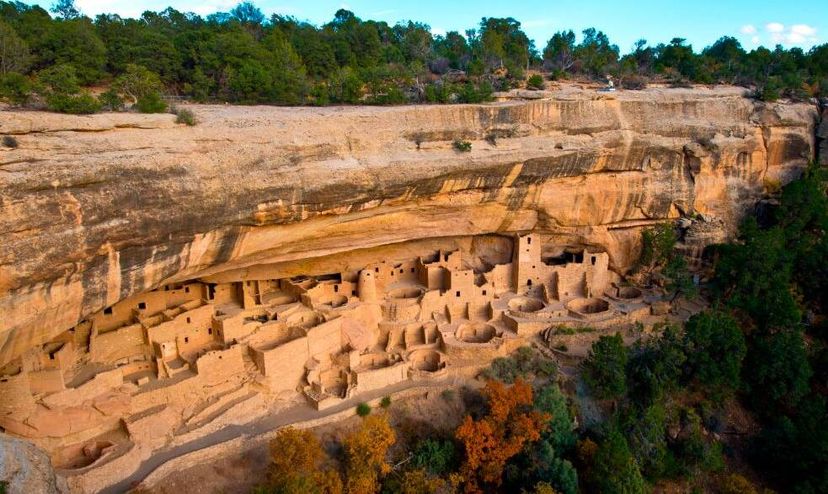

Nestled into the sheltered alcoves of the canyon walls stand the remains of elaborate stone communities constructed by the Ancestral Puebloans of Mesa Verde more than 900 years ago. Located in southwestern Colorado near the Four Corners region, Mesa Verde National Park was the first national park established to “preserve the works of man.” The park preserves more than 4,000 archaeological sites, including 600 cliff dwellings that are among the most elaborate and best-preserved sites on our national parks by state list.

History of Mesa Verde National Park

From the year 600 to 1300, a group of Ancestral Puebloans inhabited the area around Mesa Verde (the name means “green table” in Spanish). The first dwellings and villages sat on the top of the mesa. The communities evolved from pit houses dug into the earth to above-ground houses constructed of poles and mud, and eventually to elaborate multi-room, stone structures rising two to three stories high.

Around 1200, the inhabitants began moving into the recessed shelters provided by the cliffs while farming the mesa top. These dwellings ranged from single rooms for storage to villages with more than 150 rooms. Less than 100 years later, the cliff dwellers left Mesa Verde and moved south into present-day New Mexico and Arizona. The amazing structures they constructed into the cliffs lay deserted until they were discovered in the late 1700s through the late 1800s.

In 1886, an editorial in the Denver Tribune-Republican suggested the area be set aside as a national park to preserve and protect Mesa Verde and its archaeological sites from vandalism. In February of 1901, Congress failed to pass a bill to create the Colorado Cliff Dwellings National Park. Finally, in 1905, a bill for the creation of Mesa Verde National Park was introduced and the park was officially designated on June 29, 1906, by President Theodore Roosevelt.

Activities in Mesa Verde National Park

Cliff Dwellings and Archaeological Sites

There are multiple cliff dwellings and archaeological sites to see in Mesa Verde. Some of the most popular sites can only be visited by taking a ranger-guided tour, but there are plenty of self-guided options available as well. Mesa Verde sites are divided into two primary areas, the Chapin Mesa and the Wetherill Mesa.

Advertisement

Chapin Mesa

The Mesa Top Loop Road is a six-mile driving tour with access to many top sites and overlooks including pithouses, Square Tower House, Sun Temple, and a great view of Cliff Palace from Sun Point View. Also on Chapin Mesa is the Cliff Palace Loop which provides access to Cliff Palace and Balcony House. The Chapin Mesa Archaeological Museum is open year-round and features dioramas of the Ancestral Puebloans and many other artifacts and exhibits.

Cliff Palace is the largest and most widely recognized cliff dwelling in Mesa Verde. A one-hour, ranger-guided tour is available from early April through early November. The Balcony House tour is a little more adventurous and involves climbing a 32-foot ladder and crawling through a 12-foot-long tunnel. Spruce Tree House is the best-preserved cliff dwelling in Mesa Verde National Park. This site is self-guided from early March to early November and accessible via a free, ranger-guided tour in the winter months.

Wetherill Mesa

Wetherill Mesa, on the western side of the park, is a little less visited and provides access to Step House, Long House, and Badger House Community. Long House, a 150-room cliff dwelling, is covered in a 90-minute ranger-guided tour that starts with a tram ride to the trailhead. Long House offers the most in-depth tour of any cliff dwelling in the park.

Step House features a pithouse, petroglyphs, and cliff dwellings on a 3/4-mile, self-tour while Badger House Community features four surface sites on 2.5-mile (or 1.5-mile with tram) hike.

Other Activities in Mesa Verde National Park

While hiking is restricted to designated trails in the park, the designated trails, including Petroglyph Point Trail and Knife Edge Trail, allow visitors to explore other areas and the cultural history of the park. Park rangers offer a variety of evening programs and kids can participate in the Junior Ranger Program. In the winter, Mesa Verde offers cross-country skiing and snowshoeing opportunities.

Visiting Mesa Verde National Park

Mesa Verde National Park is open daily, year-round. Some areas of the park, including Cliff Palace, are closed during the winter months. Visitors should check the official operating hours while planning a visit. Park entrance fees vary based on the time of year as well. Be sure to check the park website for seasonal visitor’s guides.

Entering the park, visitors are greeted by a steep, narrow, and scenic mountain road that climbs into the park to elevations of 7,000 to 8,500 feet above sea level. Visitors should plan for at least two hours to drive into and out of the park. Fifteen miles in from the entrance, the Far View Visitor Center is a great first stop in a visit to Mesa Verde National Park. From the Far View, visitors can purchase tickets for the guided tours of Cliff Palace, Balcony House, or Long House.

The weather in Mesa Verde National Park varies greatly with the season. Summer highs climb into the 90s, so visitors should be sure to bring and drink plenty of water during their visits. Temperatures often dip below freezing overnight in the winter months with highs only in the 40s. Occasional snowstorms are possible from late fall through spring.

The official park site offers accessibility information and tips for visitors’ heart or respiratory ailments and individuals with limited mobility, hearing impairments, and visual impairments. Visitors traveling with pets should review the pet policies and information as well.

While visiting Mesa Verde National Park, travelers may want to check out other areas of interest in the region.

- Durango, Colorado is about a 40-minute drive west of Mesa Verde.

- Telluride is about a two-hour drive to the northeast.

- Four Corners, the intersection of Colorado, New Mexico, Arizona, and Utah, is an hour’s drive to the southwest.

- Canyons of the Ancients National Monument is an hour’s drive northwest.

- Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Park is a little less than four hours to the north.

- Canyonlands National Park and Arches National Park in Utah are each less than two and a half hours away.

Wildlife in Mesa Verde National Park

While Mesa Verde National Park’s primary attractions are man-made, the park also contains 8,500 acres of a wilderness area that supports a wide diversity of wildlife. Mule deer and wild turkeys are widely seen in the park from spring through fall. Other large mammals that are present, but less frequently seen by the casual visitor, include black bears, elk, gray foxes, and mountain lions.

Owls and eagles make bird watching a popular activity.

Advertisement