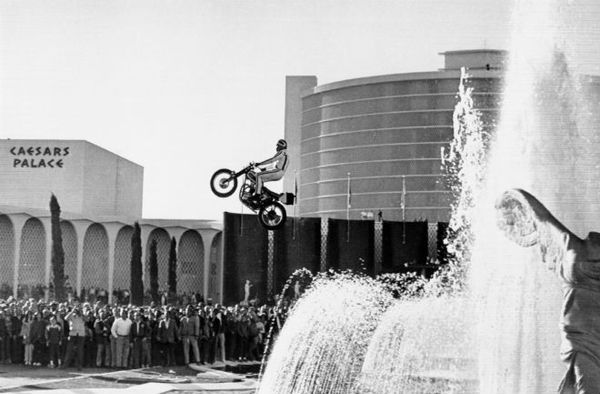

The people who jump from bridges or out of airplanes or off cliffs are, to the couch-bound and desk-chained below, a little loony. They are, at the very least, reckless adrenaline junkies. They might have — this is a common epithet — a death wish.

"I'm not into argue and debate," says Miles Daisher, a man who once flung himself from a bridge (yes, he used a parachute) 57 times in a single day. "But I can tell you, from my own personal experience … I have a life wish, man. I want to do as much as I can in this time I have on Earth."

Advertisement

For at least two decades, scientists have studied skydivers, BASE jumpers, big-wave riders and their kin to see what makes them tick. (BASE is an acronym for jumping from buildings, antennas, spans or Earth, and it's considered inherently more dangerous than your garden-variety parachuting from an airplane, because those structures are much closer to the ground.) A common theme in those studies: People who participate in "extreme sports" are motivated by a need to take risks and score an ever-elusive high.

But a new study by two psychologists refutes that notion, including the whole "death wish" thing. Instead, it suggests real, albeit somewhat intangible, benefits to explain why some take risks that make many of us shudder.

Advertisement