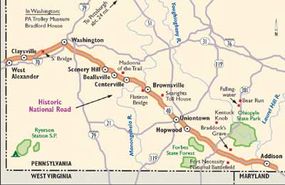

Pennsylvania's Historic National Road is the most time-honored transportation corridor in the United States -- it was one of the first colonial routes traveled by early settlers. George Washington and Daniel Boone were among its first travelers. Now, you can relive the spirit of a growing America by traveling the road and visiting the historic homes, toll houses, and scenic vistas.

As America entered the 19th century, the young nation faced one of its first challenges: how to link the people and cities along the Eastern Seaboard to those on the frontiers west of the Allegheny Mountains. Settlers moving west faced perils aggravated by the lack of a well-defined roadway.

Advertisement

And easterners were unable to take advantage of the abundant produce and goods from the western frontier without a road to transport them over the Alleghenies. The solution was the National Road, America's first interstate highway, and the only one constructed entirely with federal funds.

Construction began in 1811, and by 1818, the road stretched from Cumberland, Maryland, to what is now Wheeling, West Virginia. In time, the National Road ran the whole way to Vandalia, Illinois, a distance of 600 miles. For three decades, the history, influence, and heritage of the National Road have been celebrated at the annual National Road Festival, held on the third weekend each May. The festival features memorable festivities and a wagon train that comes into town.

Cultural Qualities of Historic National Road

The National Road was developed from existing Native American pathways and, by the 1840s, was the busiest transportation route in America. Over its miles lumbered stagecoaches, Conestoga wagons with hopeful settlers, and freight wagons pulled by braces of mules, along with peddlers, caravans, carriages, foot travelers, and mounted riders. In response to demand, inns, hostels, taverns, and retail trade sprang up to serve the many who traveled the road. Today, reminders of National Road history are still visible along this corridor, designated as one of Pennsylvania's heritage parks to preserve and interpret history throughout the region.

Qualities of Historic National Road

The first cries for a national road were heard before there was even a nation. Such a road would facilitate settlement and help the budding nation expand in order to survive and flourish. Economic considerations weighed heavily in favor of a national road, which would be a two-way street, allowing farmers and traders in the west to send their production east in exchange for manufactured goods and other essentials of life. In May 1820, Congress appropriated funds to lay out the road from Wheeling to the Mississippi.

Construction in Ohio did not commence until 1825. Indiana's route was surveyed in 1827, with construction beginning in 1829. By 1834, the road extended across the entire state of Indiana, albeit in various stages of completeness. The road began to inch across Illinois in the early 1830s, but shortages of funds and national will, plus local squabbles about its destination, caused it to end in Vandalia rather than on the shore of the Mississippi River.

The major engineering marvels associated with the National Road may have been the bridges that carried it across rivers and streams. The bridges came in a wide variety of styles and types and were made of stone, wood, iron, and, later, steel. As the bridges indicate, an amazing variety of skills were needed to build the road: surveyors laid out the path; engineers oversaw construction; carpenters framed bridges; and masons cut and worked stones for bridges and milestones.

Qualities of Historic National Road

By the early 1800s, the National Road was a lifeline, bringing people and prosperity to the regions of the country removed from the eastern coast. First a Native American trail cutting through the mountains and valleys, and then a primitive wagon trail to the first federal highway, the National Road is surrounded by the views of pristine hardwood forests blanketing rolling hills, vintage homes and barns, historic farmlands, orchards, and hunting grounds.

Find more useful information related to Pennsylvania's Historic National Road:

- How to Drive Economically: Fuel economy is a major concern when you're on a driving trip. Learn how to get better gas mileage.

Advertisement