There are plenty of cold-weather survival scenarios. You might be an avid camper or hiker lost in the dead of winter. You could be the victim of a plane crash in the Swiss Alps. Maybe you've had a car accident going over the river and through the woods to grandmother's house. Or perhaps you've simply lost electricity for an extended period of time in your own home. Knowing some basic tips and tricks can help make a difference in your comfort level, and even whether or not you make it through the night.

Nearly 50 percent of the Northern Hemisphere's total landmass can be classified as a cold region at some point in the year [source: wind all have an impact on how frigid it gets. Within these regions there are two subclassifications -- wet cold weather and dry cold weather. Wet cold describes conditions where the average temperature over a 24-hour period is 50 degrees Fahrenheit. This typically means that there are freezing conditions at night followed by thawing temperatures the following day. Dry cold means that the average daily temperature is below 14 degrees. In dry cold conditions, there is no thaw.

Advertisement

The other thing that's factored in with cold weather is wind chill -- the effect of moving air on exposed skin. Antarctic explorer Paul Siple coined the term "wind chill factor" in the late 1930s to help describe the effect that wind has on heat loss. He experimented by timing how long it took to freeze water in varying degrees of wind strength [source: USA Today]. In layman's terms, wind chill is described as how cold it "feels."

Cold weather has a dramatic effect on human health. According to a University of California, Berkeley economist, deaths related to cold reduce the average life expectancy of Americans by a decade, if not more [source: UC Berkeley News]. Cold weather also indirectly causes fatalities through accidents due to snow and ice, carbon monoxide poisoning and house fires. The elderly and the infirm are most susceptible to cold weather illness and injury, although the same UC Berkeley study reports that women make up two-thirds of the deaths after a cold spell.

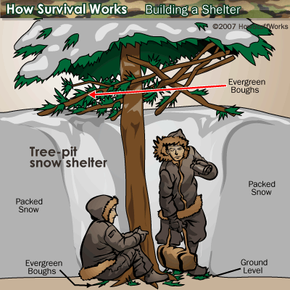

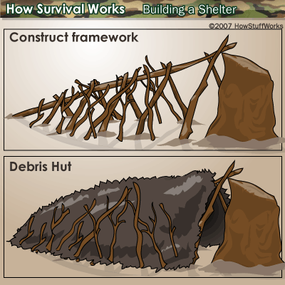

In this article, we'll go into more detail about the effect cold weather has on humans. We'll also go over the basics of surviving freezing weather conditions -- from building a snow shelter in the wild to simple tips for the average homeowner.

Advertisement